SHE might be one of the most prolific serial killers in the UK’s history but the story of Amelia Dyer is a “dark part of Reading’s history” not many people in the town will be familiar with.

Nicknamed ‘the baby farmer’, experts suggest the mass-murderer killed as many as 400 babies in Victorian Britain by strangling them and dumping them in the river.

And the woman, who lived in Caversham, might have killed more had she not been stopped by Reading Borough Police detectives.

READ MORE: Motorist driving on the M4 high on the cocaine in the dock

Her story is one that is retold in a special exhibit curated by PC Colin Boyesat Thames Valley Police’s museum in Sulhamstead.

The exhibit features key evidence, letters and other artefacts from the case that are more than 100 years old.

To visit the Thames Valley Police museum, see details at the bottom of the page.

Who was Amelia Dyer?

Dyer, who was a nurse, moved to Caversham from South Wales in 1895 before moving to Kensington Road in Reading a year later.

The nurse had previously been a carer for her mentally ill mother.

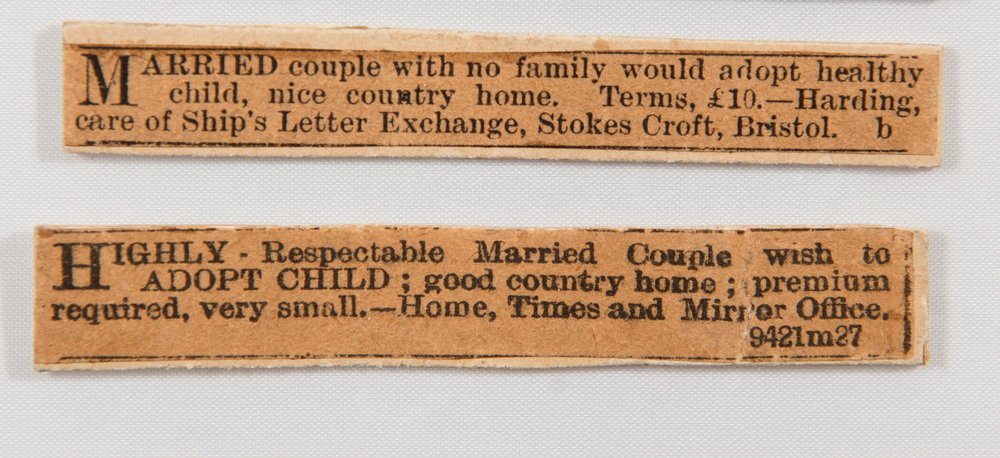

She would advertise to take unwanted children in from struggling mothers in return for a fee and clothing for the child.

A report from the BBC claimed she would travel to take babies from struggling mothers charging between £10 and £80 -- equivalent to thousands of pounds today -- for her services.

Amelia Dyer and artefacts preserved from her case. Images via TVP and Wikimedia Commons

What did she do with the babies?

The nurse pocketed the cash and killed many of the babies within days of receiving them, according to Thames Valley Police.

Dyer would strangle the infants with white tape and wrapped their bodies in paper bags before dumping them in rivers.

According to the BBC, she would kill some of the babies by starving them or drugging them with opiate-laced cordial.

In some cases, the babies were murdered within hours of being handed over, it is believed.

Dyer would then sell the babies’ clothes to pawnbrokers, PC Colin Boyes said.

READ MORE: Listen to the latest Thames Valley Court and Crime Podcast

It’s not clear how long Dyer was practising this horrific crime for, but experts suggest it may have been as long as 20-30 years.

How did she get away with this for so long?

Unmarried mothers faced tough times in Victorian Britain in a society where single parenthood and illegitimacy were frowned upon.

Fostering and adoption processes were not regulated and ‘baby farmers’, such as Dyer, would often take unwanted children off their parents’ hands for a fee with few questions, if any, asked.

According to Thames Valley Police, many baby farmers acted in good faith but the “practice was often misused” and “it was often in a baby farmer’s financial interest for the children left in their care not to survive.”

An excerpt from the TVP profile of Dyer reads: “However, in the Victorian era the trade in babies was rarely regulated, and the childhood death rate was relatively high.

“Dyer’s claims that children had died of natural causes, moved to other homes or been returned to their mothers could well have seemed believable.

READ MORE: Suspect charged after man found stabbed in Reading

“In addition, Dyer’s many changes of alias and address made it very difficult for mothers concerned at the fate of their babies to trace her.”

Amelia Dyer and artefacts preserved from her case. Images via TVP and Wikimedia Commons

How was she caught?

When Dyer lived in Bristol, she was twice legally branded ‘insane’ and this came after Dyer’s activities “threatened to catch up with her.”

In 1879 she was sentenced to six months of hard labour after doctors grew concerned at the number of deaths certified in her care.

She gave up with death certificates after moving to Reading and turned to disposing of the bodies herself by dumping them in packages in the river.

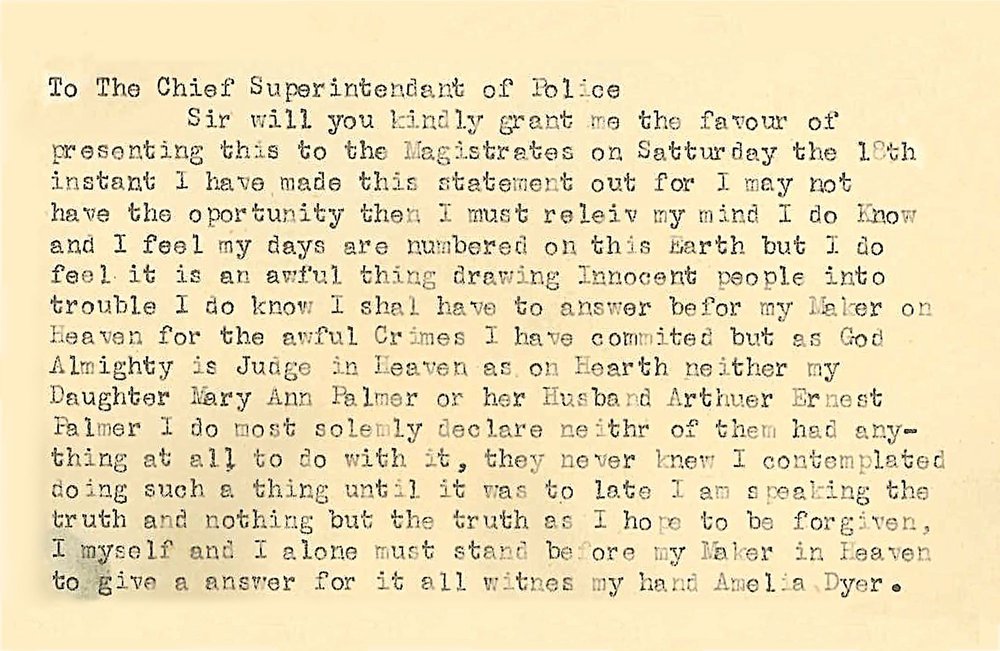

At her trial following her arrest in 1896, her family and friends claimed they had been suspicious of the nurse and it emerged she had “narrowly escaped discovery on several occasions.”

But she was finally caught in March 1896 when a bargeman found a packet in the River Thames with a baby girl, later identified as Helena Fry, inside it.

READ MORE: Berkshire's Air Ambulance treats 5,000th patient

A detective found a faintly-written name and address for Dyer on the package but police did not confront her immediately as they believed she would flee if questioned.

Instead, they sent a female decoy to Dyer’s address to enquire about her services.

When she opened the door expecting to find the young woman, she was instead met by two Reading Borough police officers.

What happened next?

The nurse was arrested and charged with murder. The following month, the Thames was searched and six more babies were discovered.

Amelia Dyer and artefacts preserved from her case. Images via TVP and Wikimedia Commons

Items from Dyer’s home suggested she murdered many more, with evidence suggesting she murdered at least a dozen infants.

Although it was believed she could have murdered as many as 400 babies in her lifetime, the 57-year-old was eventually executed on June 10, 1896, for the murder of a single child following a trial in which Dyer pleaded insanity.

What were the consequences of this case?

PC Colin Boyes told the Chronicle: “This is a really dark part of Reading’s history not many people know about”.

A number of acts passed through parliament in the years following Dyer’s crimes, including the Protection Act (1897) and the Children’s Act (1908).

READ MORE: Seafront assault hours after Reading man followed woman around car park

These laws required local authorities to be notified of a change of address of an infant.

Rules surrounding fostering and adoption were strengthened and “baby farming became a thing of the past”, according to TVP.

The newly-established NSPCC became “more influential” after this case, too, according to the BBC.

To see the Amelia Dyer exhibit for yourself, the Thames Valley Police museum is free to visit without an appointment between 10am and 12pm every Wednesday.

It is necessary to make an appointment to visit the museum outside these hours and a small visitor fee is required.

The museum is based in the White House, at The Thames Valley Police Training Centre in Sulhamstead, Nr Reading, Berkshire, RG7 4DX.

To make a booking please email TVPMuseum@thamesvalley.police.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel