AS Reading mourned the Forbury Gardens terror attack, many found hope in one of the town’s iconic monuments.

The Maiwand Lion – or as many people fondly know it The Forbury Lion – has been adopted as a symbol of unity by people following the tragic events in Forbury Gardens.

The lion was placed in memory of soldiers who had died in 1880 fighting for their country and now within its shadow sadly three more people have lost their lives.

But the lion quickly became not only a monument, but a symbol of Reading found amongst a sea of flowers left by mourners paying their respects to those who were killed.

A handwritten note outside Forbury Gardens read: “Reading weeps. But Reading roars with diversity, culture and community.

“We roar like the lion at the heart of this beautiful park.”

READ ALSO: Reading 35th in list of healthy high streets.

A note which could be a sign of the town’s hope in tragic times and the importance of the town’s lion to the community.

Three people were killed and several others injured when an attacker stormed the popular park and stabbed multiple people.

The park had always been a regular spot for picnickers and walkers especially in the summer months and those attacked had been enjoying an afternoon in the sun.

Tributes flooded in for the victims and the iconic lion which stands tall in the centre of the park has been seen regularly within these touching pieces.

A black and white silhouette drawing of the lion started circulating on social media the week following the attack.

READ ALSO: Reading's Forbury Gardens lion image goes viral as town shows unity.

The image shows the lion and a broken heart with ‘RDG’ written next to it.

Richard Bennett, the Chair of Reading’s Civic Society, said: “As a lover of statues and sculptures it is most welcome that a symbol of Britain’s past is seen as a symbol of Bravery and Hope today.”

He added: “The Maiwand lion is in a prominent and public place and so has been regularly seen, and loved, over many decades.

“This I think elevates it, in more ways than one, from being a memorial to being a well-known symbol of Reading itself.

“That the lion almost seems to be smiling and friendly perhaps makes it approachable in some way.”

But despite it being a familiar face to visitors and residents of Reading, its history might not be so.

History of Forbury Gardens and its lion

The lion has sat pride of place in Forbury Gardens for 134 years having been unveiled in December 1886 as a war memorial, according to Reading Museum.

The museum’s website explains the lion is named after a small village in Afghanistan where 328 men from the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment died in July 1880.

It adds the Battle of Maiwand “was part of a British campaign to stop Russian influence in Afghanistan, as this threatened British control of India”.

In 1880 British and Indian troops stationed in Kandahar, Afghanistan, were sent to oppose an army led by Ayoub Khan the brother of Afghanistan’s deposed ruler, the museum states.

The British force was led by General Burrows and had to secure the Maiwand pass to stop Ayoub’s advance on Kabul.

The museum explained: “Burrow’s force of 2,565 men was slowed by high temperatures and a baggage train of 2,500 animals carrying supplies.

“Ayoub had over 6000 men, the advantage of local knowledge and good strategic positions.

READ ALSO: Neil Warnock plots swoop for Reading FC stalwart - reports.

“Despite British attempts, their lines were broken, and the majority of the British were forced to retreat in disarray to Kandahar.”

British casualties were high with 44 per cent of its forces killed.

Grand unveiling

The 31-foot lion was unveiled in December 1886 having been sculpted by George Blackall Simonds.

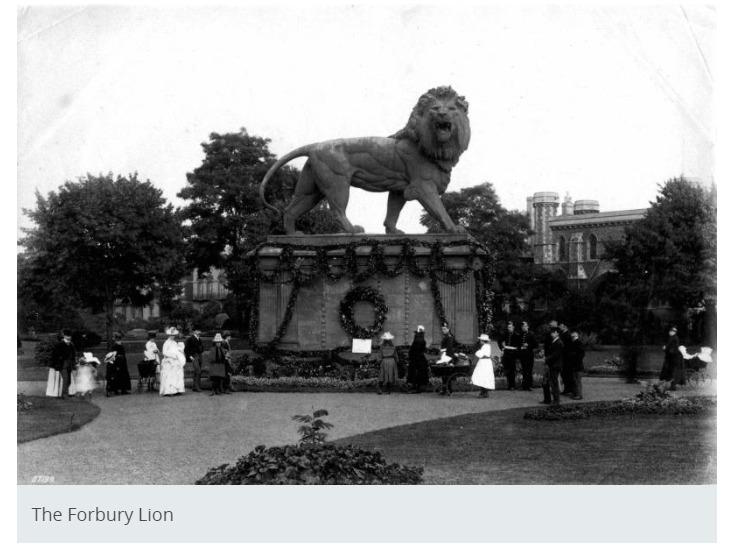

A black and white picture on the museum’s website shows the lion decorated with a garland that ran around the top of the pedestal.

It said the pedestal was originally faced with terracotta and brick, but this was replaced with Portland stone in 1910.

The image shows men dressed in suits and women in Victorian dresses with prams gathering around the monument and looking up at its grand stature.

Myths

The museum website explains the statue has “one of the great Reading myths associated with it”.

It was rumoured that Blackall Simonds killed himself because the lion’s pose wasn’t accurate, but this is not true.

The museum said: “He studied the movement of lions at London Zoo and it shows the moment when a lion is moving at speed. Experts from London Zoo have even confirmed that the pose is accurate.”

Mr Bennett said: “The story of the lion’s stance being wrong is total nonsense, but perhaps it adds to the affection people have for it.”

The statue has been part of Reading’s culture for more than 100 years and will be there for many more.

Despite Reading’s tragic events, the community will continue to be strong together and “roar like the lion at the heart of this beautiful park”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here